What is community ownership, and how can investing in it help bolster local communities and create a more equitable future?

From sharecropping to redlining to urban neighborhood disinvestment, control over property ownership has been a tool used to oppress Black and Brown communities throughout the United States’ history. As decades and generations of systemic oppression have converged, it’s going to take bold new strategies — ones that place people firmly before profit — to begin reversing historical harms and building a more equitable future.

Community ownership isn’t a new concept, but it’s one that’s gaining more and more traction as housing and property prices soar out of reach for so many people — especially Black, Indigenous, people of color (BIPOC) and historically low-income communities. With a variety of potential models and the growing number of success stories, it’s one way community builders and changemakers are accelerating progress toward building just, self-determined, and regenerative local economies.

What is Community Ownership?

On its face, community ownership is a simple idea.

“Community ownership” refers to a model of collective ownership and management of resources, assets, or services by a community or group of individuals who live or work in a particular area.

In this model, the community members have a stake in the ownership and decision making of the resources, which may include land, buildings, businesses, or other community assets. Community members collaborate and participate in management and governance processes, with the goal of improving their social and economic well-being and maintaining the sustainability of their shared resources.

Community ownership can take many forms, but the underlying principle is that the community members have a shared sense of responsibility for the assets and resources that they collectively own, and work together to achieve common goals and values.

One common type of community ownership in the U.S. is community ownership of land or real estate property.

As Brookings Institute researchers Tracy Hadden Loh and Hanna Love have noted, defining this kind of community ownership in practice can be difficult. They’ve identified four questions that can help define the concept:

- What are the goals of community ownership? By definition, community ownership exists for the “common good” of the community, but how “common good” is defined varies, and can help define the model of community ownership.

- Who is the “community”? The definition of community varies, and can be as large as an entire city or as small as a single neighborhood or building.

- Who “owns” the property in community ownership? Community ownership still needs to fit under existing laws and regulations, which means that someone has to actually own the community’s resources. How ownership is divided and earned varies based on the model of community ownership at play.

- How do individual wealth and community ownership intersect? Community ownership doesn’t necessarily mean that individuals give up all of their own property rights, but this varies depending on the model of community ownership — which also helps determine the balance between community and individual rights and responsibilities.

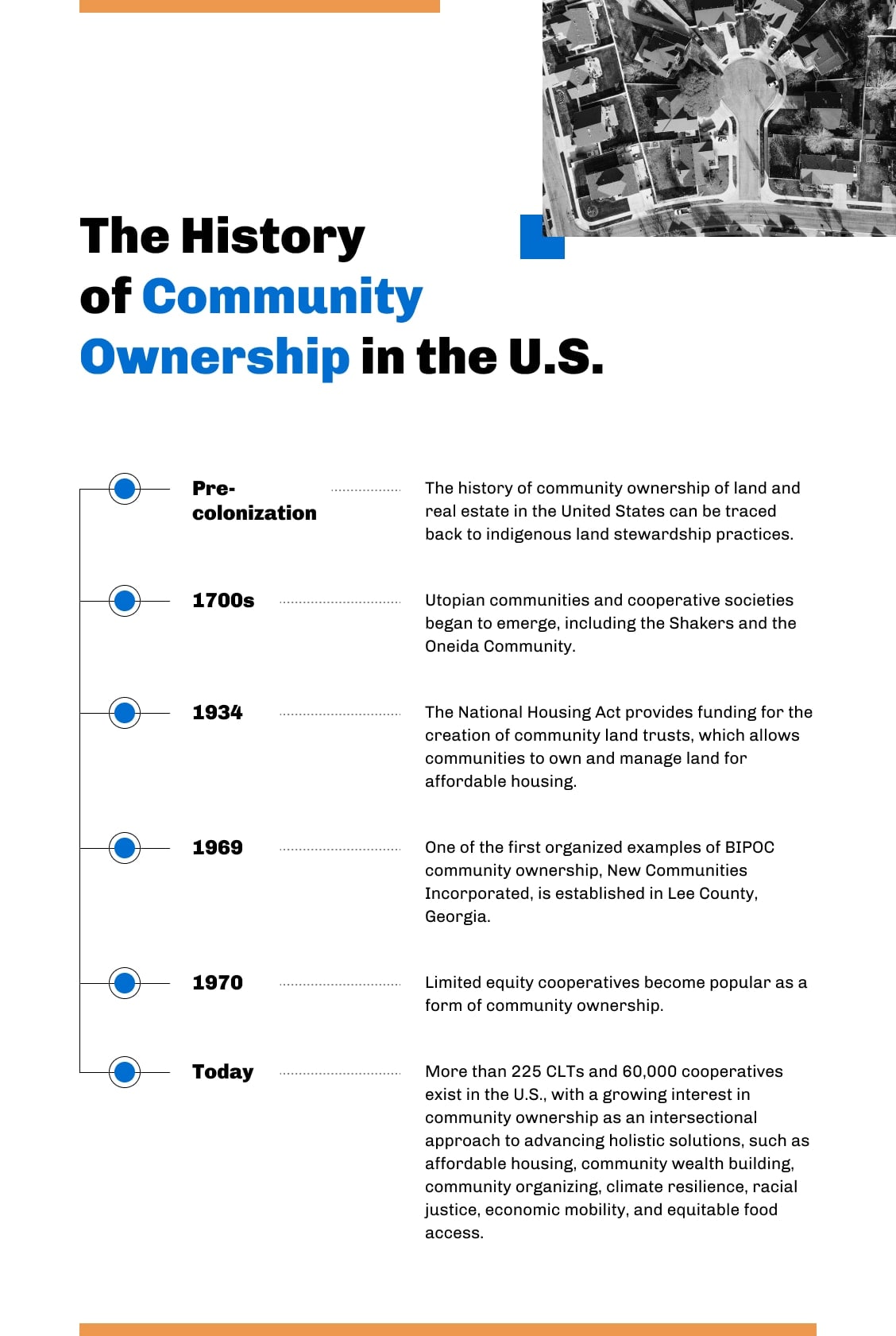

The History of Community Land Ownership

Community ownership has a long history around the world. One of the earliest examples is in India, where land was held as common property among tribes until around 1500 B.C.E. In North America, Mexican ejidos, or “village lands,” were formally established in the 1920s — but long before that, they existed as a traditional indigenous system of land tenure where collectively owned parcels were worked by tenants.

The history of community ownership of land and real estate in the United States can be traced back to indigenous land stewardship practices. These practices continued post-colonization in the 1700s, when utopian communities and cooperative societies emerged. The Shakers, for example, established communal farms and villages in the 18th and 19th centuries, where land was owned and used collectively. Similarly, the Oneida Community, founded in 1848 in upstate New York, was a utopian society that shared land and resources in a communal manner.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, land trusts and mutual housing associations began to emerge as vehicles for community ownership. The National Housing Act of 1934 also provided funding for the creation of community land trusts, which allowed communities to own and manage land for affordable housing.

Community land trusts gained even more traction in the 1960s South amid the Civil Rights movement. One of the first organized examples of BIPOC community ownership was New Communities Incorporated, a community land trust established in Lee County, Georgia in 1969. The trust gave Black farmers collective power to fight back against discrimination, predatory lending, and agricultural industrialization that prevented them from securing land. In the next decade or so, community land trusts became a more common way for historically oppressed communities to combat racist lending practices and major industries, like timber, who fought to control vast swaths of rural America.

In the 1970s and 1980s, limited equity cooperatives also became popular as a form of community ownership. These cooperatives were typically created by tenants who purchased their buildings from landlords, often with the help of government financing. Unlike market-rate cooperatives, which allow for resale at market value, limited equity cooperatives limit the resale value of units in order to maintain affordability for future buyers.

Throughout the 20th century, other models of community ownership have emerged, such as community development corporations (CDCs), community benefit corporations (CBCs), and community foundations. CDCs were first established in the 1960s as a response to the lack of investment in low-income urban communities. These organizations are typically non-profit entities that engage in a range of community development activities, including affordable housing development, commercial development, and neighborhood revitalization. CBCs are for-profit entities that are dedicated to using their business operations to achieve social or environmental goals, such as sustainable agriculture or renewable energy development. Community foundations are non-profit organizations that pool charitable donations from individuals and organizations in order to make grants to support community development.

Despite the long history and diversity of community ownership models in the United States, the scale of community ownership remains relatively small compared to traditional models of ownership. Structural racism, discriminatory policies and practices, and market pressures have all been barriers to the widespread adoption of community ownership models. However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in community ownership as an intersectional approach to advancing holistic solutions, such as affordable housing, community wealth building, community organizing, climate resilience, racial justice, economic mobility, and equitable food access.

A Snapshot of Community Ownership in Action

The East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative (EB PREC) is a cooperative corporation located in California. The cooperative raises capital through investments and membership shares, which are sold for $1,000 each. The capital is used to purchase properties in Oakland and the East Bay.

Members who are residents in EB PREC’s properties secure long-term leases through monthly payments. EB PREC sets minimum standards for maintenance, but most property decisions are made democratically by residents. Residents can sell their leases for a modest return tied to the Consumer Price Index, plus compensation for any improvements they’ve made.

The result is housing that’s co-owned and co-stewarded by resident homeowners, investors, community members, and EB PREC staff. EB PREC provides training to residents in how to manage their homes without landlords. For every property EB PREC buys, community housing is removed from the speculative market, protected, and reserved to help disenfranchised community members preserve affordability, build community wealth, and reinvest in their own community.

Today, the East Bay Permanent Real Estate Cooperative owns three properties that provide permanent, affordable housing for BIPOC residents, working artists, art educators, and other “culture-keepers” in the community.

The Breadth of Community Ownership Models

Community ownership today comes in many forms, including coops, real-estate investment trusts, community-owned stores, and more. Some of the most common models of community ownership are below, and is an ever-evolving list as the sector continues to grow.

Cooperatives

Cooperatives are businesses or housing owned and stewarded by their members. They can take many forms, including consumer cooperatives, worker cooperatives, and residential cooperatives. The members of a cooperative share in the decision making of the property or business, and often work together to provide goods and services to their community of owners.

Ownership:

In a cooperative, ownership is vested in the members of the cooperative, who are also the customers, employees, or residents of the cooperative. Members typically have an equal say in choosing leadership, though the majority of cooperatives do not have direct member governance (consumer cooperatives, credit unions, or electric cooperatives, for example). Unlike traditional corporations, cooperatives are not owned by external shareholders who are seeking to maximize their profits.

Financing:

Cooperatives can be financed through many different means, including member equity, loans, and grants. Members may invest capital in the cooperative, which allows it to purchase assets or make improvements. Members may also provide loans to the cooperative, which can be repaid with interest.

Governance:

Cooperatives are democratically governed, with each member having an equal vote in the decision making process. Typically, cooperatives have an equal vote for determining leadership, but this can depend on the structure of the cooperative; for example, some have uneven voting representation to prioritize local voice if there is a mix of local shareholders and consumer shareholders. The board is responsible for setting policies and overseeing the management of the cooperative. In some cases, cooperatives may also have committees or working groups that are responsible for specific areas of governance.

Community Land Trusts

Community land trusts (CLTs) are non-profit organizations that hold land for the benefit of a local community. They can be established for residences, commercial property, or both.

Ownership:

In a CLT, the land is owned by the CLT itself, while individual community members own the buildings and improvements on the land. This separation of ownership ensures that the land remains in the public trust and is not subject to market speculation or gentrification. The CLT’s ownership of the land is typically perpetual, meaning that the land is held in trust for future generations.

Financing:

CLTs can be financed through avenues like grants, donations, and loans. Because CLTs are non-profit organizations, they are not focused on generating profits for shareholders or investors. Instead, they are focused on providing affordable housing or preserving, protecting, or producing open space for the benefit of the community. This mission-driven approach can make it easier for CLTs to secure funding from government agencies, philanthropic organizations, and socially responsible investors.

Governance:

CLTs are democratically governed by a board of directors, which is typically made up of community members and stakeholders. The board is responsible for setting policies and overseeing the management of the land held by the CLT. Because CLTs are community-led organizations, they often have strong community engagement programs that involve community members in the decision making process. They also often have a requirement about community representation on the board of directors.

In addition to democratic governance, CLTs are guided by a set of principles and values that emphasize community control and stewardship of the land. These principles include community control of the land, democratic decision making, long-term affordability, and sustainable development.

Community Development Corporations

Community development corporations (CDCs) are non-profit organizations that are focused on community economic development.

Ownership:

CDCs do not have a standard ownership structure in the traditional sense. Instead, they are community-based organizations that are focused on serving the needs of the community. CDCs may engage in a range of activities, including affordable housing development, small and local business support, and community revitalization initiatives.

Financing:

CDCs can be financed through a variety of means, including grants, donations, loans, and tax credits. Because CDCs are focused on community economic development rather than generating profits, they often have access to funding sources that are not available to for-profit businesses, such as government agencies, philanthropic and advocacy organizations, and socially responsible investors.

Governance:

CDCs are governed by a board of directors, which is typically made up of community members and stakeholders. The board sets policies and oversees management, with involvement from community members in the decision making process.

CDCs also follow principles and values that emphasize local ownership and control of resources, community participation in decision making, community-based economic development, and social and economic justice.

(for more examples of emerging Community Ownership models, check out this report from Kresge Foundation)

Benefits of Community Ownership

In the different models of community ownership, there’s one common thread: They share the core principle of community control and decision making over assets or resources. They’re all designed to ensure that resources are owned and managed by members of the community, rather than by individuals or corporations who may not have the community’s best interests in mind.

Studies of community ownership models over time have identified a number of benefits that provide evidence for the effectiveness of community ownership in bolstering local economies, building generational wealth, and protecting communities and the environment.

Economic Benefits of Community Ownership

The research is strongest in the area of economic benefits of community ownership.

Community ownership models have been found to enhance retention for homeownership, especially for low-income buyers. For example, CLTs help reduce mortgage foreclosure and prevent the loss of household wealth by having a third party that stands between the owners and lenders, reviews and approves proposed mortgages to prevent predatory terms, and seeks to support owners if they get behind in their payments.

Community ownership models also help close the racial wealth gap by distributing land-based wealth intergenerationally, especially in predominantly Black communities where assets are undervalued. In terms of small business development, community ownership models reduce barriers to entry by preserving low-cost retail spaces and bringing capital investments into communities to address commercial needs.

Lastly, community ownership models bring economic benefits to state and local governments in weaker markets by reducing vacancies, strengthening ‘community curb appeal’ and making more efficient use of existing infrastructure.

Civic Benefits of Community Ownership

In addition to the economic benefits, community ownership has been found to have a number of important civic benefits that help build strong communities.

Community ownership models often rely on the active participation of community members in decision making processes, building increased civic engagement and political power where generations of white supremacy, systemic racism, and economic injustice have shut Black, Indigenous, immigrant, and people of color — as well as other marginalized communities including disabled folks, working people, and LGBTQIA+ people — out of being able to shape city, county, and state laws and institutions.

Community ownership exists to serve the “public good” of the community, which gives all residents and stakeholders an active role in the stewardship of shared assets like parks and community centers. Research shows that this can inspire residents to organize for additional collective infrastructure, public spaces, health and wellness, and other shared goals that will help the community thrive.

Social Benefits of Community Ownership

Because community members are involved in decision making in virtually every model of community ownership, these models naturally foster social cohesion and a sense of belonging among residents and neighbors. They can also help reduce disparities in access to resources and opportunities, particularly for historically marginalized communities.

This leads to greater local control over resources and governance, enabling communities to prioritize their own needs and values with equity and sustainability at the center of their practices.

What's Holding Community Ownership Back?

Despite all the benefits, community ownership still faces challenges and roadblocks. Both policy and structural barriers prevent more widespread adoption of community ownership nationwide.

Access to Capital

One of the largest barriers is access to capital. Community ownership often requires significant liquid, upfront capital for land, buildings, renovations, and conversions. Access to financing can be a major challenge for communities that lack wealth or connections to financial institutions.

Even when capital is available, mission-driven investors and organizations aren’t always compatible with the pace of real estate deals. Real estate sales transactions average about a month in length, which isn’t always enough time to assemble capital from sources like philanthropy and grants, which simply aren’t designed to move that quickly.

Regulatory Barriers

Another major challenge is barriers in systemic and regulatory processes that aren’t historically designed for facilitating community ownership.

There is a lot of government funding for affordable housing in the U.S., but it tends to favor developers working within specific approaches — for example, new construction and multifamily rentals with high numbers of units. Existing models of community ownership don’t easily fit this profile, so they can’t easily access available funding — which limits their ability to grow.

There’s also the levels of oversight and regulation that different community ownership models must adhere to. Community land trusts are defined in federal law, but many of the newer, emerging financial models for community ownership are subject to state regulations or the SEC, where many regulations are designed to protect investors, which is antithetical to the governance goal of community ownership. Investors are typically primarily concerned with maximizing financial returns on their investments. They are motivated by profit and may prioritize short-term financial gain over the long-term well-being of the community. This is especially true in the case of outside investors who do not have a direct connection to the community in which they are investing.

Additionally, investors may have different priorities and values than the community. For example, investors may prioritize economic growth and development over environmental concerns or social justice issues. They may not consider the impact of their investments on the community’s quality of life or cultural identity. Investors may also have different time horizons than community members, as they may be looking to exit their investment in a relatively short period, while the community has a long-term interest in the health and sustainability of the assets they own.

Limited Access to Expertise

In community ownership models, community members work with funders, investors, and other activists who use different strategies, tactics, tools, and vocabulary. Sometimes even getting every stakeholder aligned can be a significant barrier.

Community ownership also can require a high degree of expertise in fields such as finance, real estate, and law. Not all communities — especially those that have been historically disenfranchised — have access to the necessary expertise.

Structural Racism

Structural racism has been a significant barrier to community ownership by creating and perpetuating systemic inequalities that have limited access to wealth, resources, and opportunities for communities and people of color.

Systemic racism bleeds into and affects all other barriers to community ownership; for example, racial bias and discrimination have impacted the ability of communities of color to access funding and resources needed to start and sustain community-owned businesses and organizations. Black and Brown communities have historically been labeled as “high risk” by lenders and financial institutions due to systemic racism and biases. This perception has resulted in limited access to financial resources, making it difficult for these communities to secure the capital needed to start and sustain community-owned businesses and organizations.

How Possibility Labs Addresses Barriers to Community Ownership

At Possibility Labs, we support community ownership as an essential means for our communities (and individuals in those communities) to own and self-govern our own assets so we can determine our own futures. We believe that this leads to a regenerative local economy with better paying jobs, locally owned businesses, and community-owned housing.

Possibility Labs can help community changemakers interested and invested in community ownership accelerate their progress. We also help foundations, donors, philanthropists, and other stakeholders amplify their impact via community investments.

We do this in four main ways:

- Capital and growth services: We offer fiscal sponsorship, resourcing, and hosted fund capabilities as well as community-driven investment vehicles such as Donor Advised Funds that make it easier (and faster) to deploy and manage flexible, integrated capital, including multi-year grants, recoverable loans, and recoverable grants, to name a few.

- Strategic advising: We can advise on entity structures, financial and legal compliance, information and operation infrastructure, fund design, and investment strategies to help changemakers design and implement custom solutions that fuel growth in their unique communities.

- Modernized data management: We offer a cohesive tech stack in an all-in-one portal that helps bring community focused organizations into the digital age.

- Community learning: We help build cross-sector relationships and facilitate networks for support, learning, accountability, and expertise so changemakers can align and connect with a diverse ecosystem of knowledge and skills.

Possibility Labs focuses on operationalizing multi-entity solutions advancing social, climate, gender, racial, and economic justice. Discover what’s possible with Possibility Labs: Schedule an introductory conversation with a member of our team today.